African Women and the Middle Passage

2025 Women’s History Month

Annually during Women’s History Month, the Middle Passage Ceremonies and Port Markers Project (MPCPMP) acknowledges women who have had an impact on families, communities, and this nation. As an organization that addresses Middle Passage history, this Women’s History Month 2025 we begin with the little-known history of African women who were crucial in resisting capture and facilitating survival during the Middle Passage.

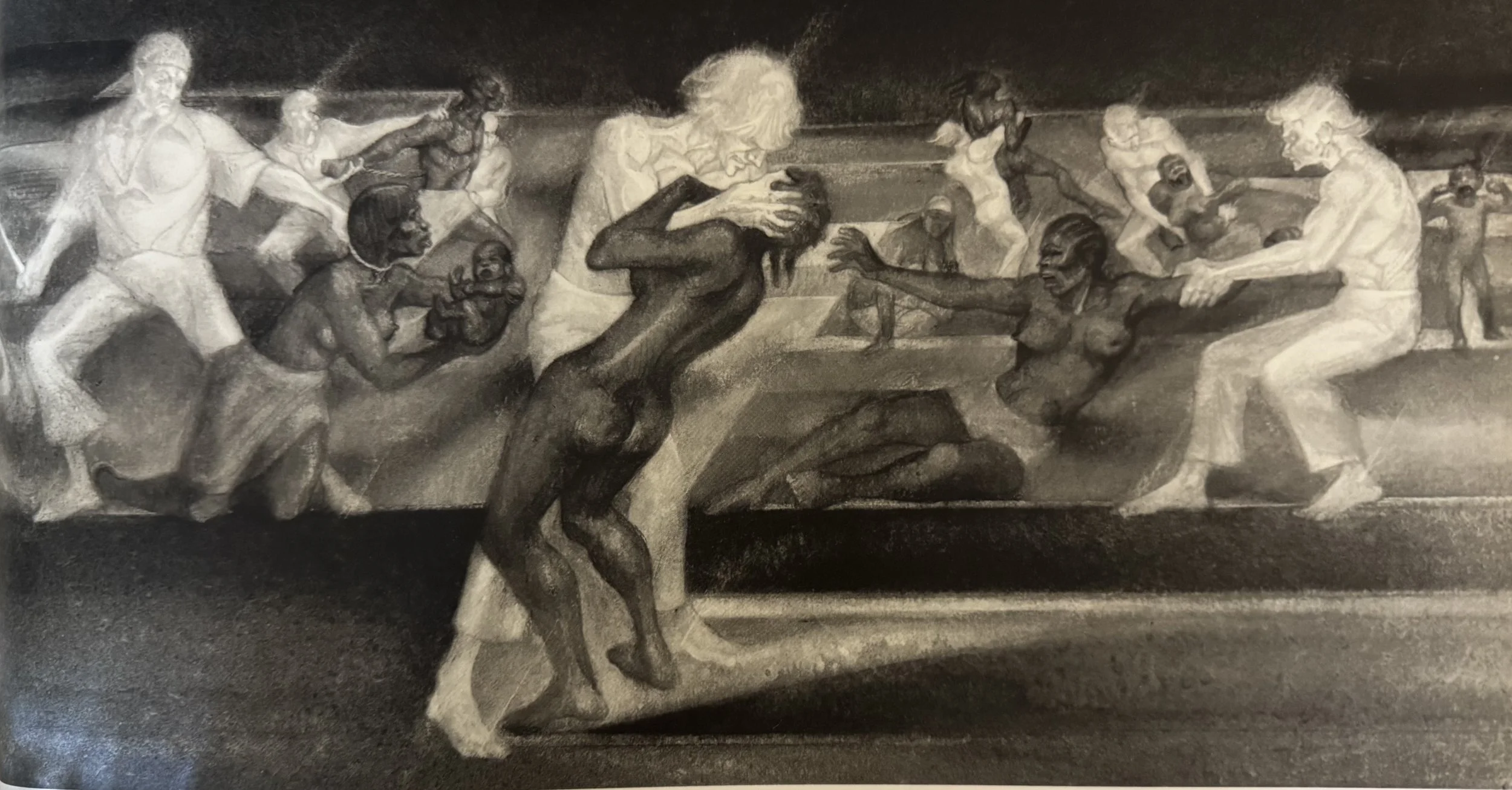

Image: Tom Feelings

If the Atlantic were to dry up, it would reveal a scattered pathway of human bones marking the various routes of the Middle Passage. But those who did survive multiplied and have contributed to the creation of a new human society in the Americas and the Caribbean. It is a testament of the vitality and fortitude of the Africans that ten to twenty million lived through the heinous ordeal that many consider the greatest crime ever committed against a people in human history.

- John Henrik Clarke

The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database estimates that 12.5 million Africans made it to these shores alive, and approximately 4 million, one in three, were women. The data, historian Jane Landers writes, also show “a striking and gendered pattern of African resistance.” According to first-hand accounts, resistance and survival often depended on women. Routinely they provided comfort to fellow captives, prepared and distributed the food, suffered personal trauma, and led the songs of mourning and sorrow.

On the trans-Atlantic voyages, African women readily assisted and participated in revolts as well. Typically left unchained and above deck, they were less restricted, sometimes allowed to move about freely, and had more access to crew and officers, allowing them to assess the ships’ vulnerabilities, such as the crews’ routines and weapon storage locations. Some historians suggest that because of the freedom of movement on board it was women who planned, organized, and facilitated many of the Middle Passage rebellions. African captive Ottobah Cugoano in his account of a planned revolt states that, “It was the women and boys which were to burn the ship…”

Beatings and other forms of physical abuse by the crew and officers were a common occurrence. In The Interesting Narrative of The Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, The African, Equiano observes events during the Middle Passage, and in one report comments:

The Black women used broad sticks as spoons, which they turn around, licking them with their fingers, and calling out, “Sufie, Sufie, Grand;” then a man with a cat of nine tails gives them a scourge … they go forward with the food.

Captive women also endured the personal trauma of repeated rapes, separation, and death. Angela Davis in her work on female slavery explains that it was common practice on many vessels to permit crew access to girls and women for sexual coercion and rape with impunity by the crew and officers. According to Cugoano, “It was common for the dirty filthy sailors to take the African women and lie upon their bodies.” In his poem “The Middle Passage,” Robert Hayden uses “lust” as a euphemism to describe rape aboard ship that served as a tool of oppression and dominance:

That Crew and Captain lusted with the comeliest

of the savage girls kept naked in the cabins;

That there was one they called The Guinea Rose

and they cast lots and fought to lie with her.

By the end of the voyage many African women had conceived, thus increasing their value to the New World buyer. Rather than bring a child into enslavement, they sometimes performed abortion and infanticide.

African women and girls were completely vulnerable and incapable of protecting themselves. Conversely, this sexual coercion had a two-fold effect since it also targeted the African men who suffered from an inability to prevent or stop the abuse. The goal was to destroy the women’s will to resist and to demoralize the men. However, it created a form of equality because as acts of brutality, oppression, and punishment were applied to men and women indiscriminately, the resistance and passion against enslavement was equal for both sexes.

In the Account of the Slave Trade on the Coast of Africa (1788), the reports of the abolitionists and enslavers who testified before Parliament about the human trade and the response of women to their capture, removal, and separation from their communities were the most poignant:

A woman was dejected from the moment she came on board, and refused both food and medicine; being asked by the interpreter what she wanted, she replied, “nothing but to die,” and she did die.

It frequently happens that the negroes, on being purchased by the Europeans, become raving mad, and many of them die in that state, particularly the women. While I was one day ashore at Bonny, I saw a middle aged stout woman, who had been brought down from a fair the preceding day, chained to the post of a black trader’s door in a state of furious insanity.

And, to conclude on this subject, I could not help being sensibly affected, on a former voyage, at observing with what apparent eagerness a black woman seized some dirt from off an African yam, and put it into her mouth; seeming to rejoice at the opportunity to possessing some of her native earth.

During the 350 years of the trans-Atlantic human trade, in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds, African women and their descendants maintained the cultural identities and traditional practices of their people, adapting as necessary to the changes that the shared experience of capture and the Middle Passage voyages demanded. Michael Gomez writes in Exchanging Our Country Marks: The Transformation of African Identities in the Colonial and Antebellum South that these Africans, who previously identified themselves by their ethnicity, began to form a new Black community that developed on the ship even prior to arrival in the New World.

Today, we honor women who with determination, resistance, strength, and courage transmitted their African values and traditions to their descendants.

Throughout this year, MPCPMP will continue to highlight women who over centuries have fought for freedom, equality, cultural preservation, and for our very lives.

If you would like to support our mission of healing and truth-telling please visit our donation page.